|

|

|

Father René Soler

|

Aristide's people:

|

| by Peter Costantini | Port-au-Prince | December 13, 1995 |

|

|

|

Father René Soler

|

Aristide's people:

|

| by Peter Costantini | Port-au-Prince | December 13, 1995 |

|

beginning

|

|

|

"We must

prepare the coffee of reconciliation through the filter of justice."

—President Jean-Bertrand Aristide ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif)

|

|

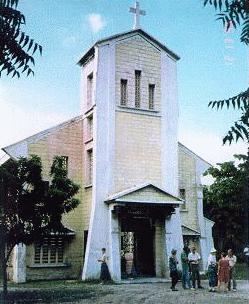

| St. Jean Bosco |

In the poor Port-au-Prince neighborhood of La Saline stand the ruins of a yellow and white cinder-block church. The roof is gone and the walls are blackened here and there with soot. The gates are chained shut. Spelled out on them in wrought iron is the Latin inscription: "Da mihi animas, caetera tolle" ("Give me the souls, take the rest").

In this church on September 11, 1988, thousands of faithful gathered to hear a mesmerizing young priest who spoke out for Haiti's poor majority against the military dictatorship of General Prosper Avril. As Jean-Bertrand Aristide said mass, a gang of Tontons Macoute (Bogeymen), the death squads tied to the military, broke down the gates and swarmed in with machetes and guns. They began slaughtering worshippers and piling bodies outside the church. When they were done, they threw the bodies inside and set St. Jean Bosco on fire.

According to Ron Voss, an American former priest who has

worked in Haiti since 1980, the Macoutes ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) stabbed a pregnant woman,

who was brought to a hospital. Soldiers came to the maternity ward where

she had been taken, and made all the women lift their robes so they could

check for wounds. But the woman had already been taken to another hospital

clandestinely. The baby was wounded but survived. The mother named it "Hope."

stabbed a pregnant woman,

who was brought to a hospital. Soldiers came to the maternity ward where

she had been taken, and made all the women lift their robes so they could

check for wounds. But the woman had already been taken to another hospital

clandestinely. The baby was wounded but survived. The mother named it "Hope."

| "They always take the people closest to Aristide." |

Afterwards, Aristide said: "We are more blessed when we preach to the hungry from a pile of cinders than when we preach to the wealthy from a magnificent altar in a magnificent church. ... The side of the martyrs triumphed." His congregation, he said, was supposed to disappear in a hail of bullets. But it survived and became a symbol. Today, the ruined church has become an informal monument, but next door the church school continues to teach children.

|

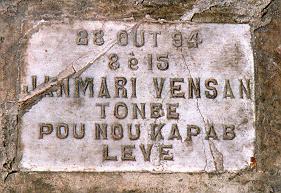

| plaque at site of assassination of Father Jean-Marie Vincent, a friend of Aristide |

On the eve of the December 17, 1995 elections to choose a successor to President Aristide, the vocal majority of Haitians hopes they have put the times of fire and blood behind them. But while many appreciate foreign help in overthowing the dictatorship, they fear that U.S. and U.N. forces have not finished the job. The army, demobilized by Aristide against Washington's resistance, is still living among them. Death squads occasionally come out of hiding to make a statement. The authors of the bloodshed are living close by, waiting for an opening to return. And the new police are inexperienced and lightly armed.

The St. Jean Bosco massacre was a moment of candid, public

terror, but it was not atypical of the Haitian experience since the beginning

of the Duvalier ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) family dictatorship in 1957. Although Jean-Claude Duvalier

left for Paris on an American cargo plane in 1986, the succession of military

strongmen has been interrupted only by the seven months after Aristide's

inauguration in February 1991. During that period, human rights abuses

dropped dramatically and the country began to slowly dig itself out of

the ashes.

family dictatorship in 1957. Although Jean-Claude Duvalier

left for Paris on an American cargo plane in 1986, the succession of military

strongmen has been interrupted only by the seven months after Aristide's

inauguration in February 1991. During that period, human rights abuses

dropped dramatically and the country began to slowly dig itself out of

the ashes.

It was thrown back into the fire on September 30, 1991,

when a coup headed by General Raoul Cédras ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) overthrew the constitutional

government. Cédras and other coup leaders flew away on an American plane

when U.S. forces landed and restored Aristide to power on October 16, 1994.

overthrew the constitutional

government. Cédras and other coup leaders flew away on an American plane

when U.S. forces landed and restored Aristide to power on October 16, 1994.

Anyone connected to the President has been a target. "They always take the people closest to Aristide," said Voss.

| "Seventy to 80 percent of the judges are holdovers from the Duvalier dictatorship or the coup, and it's hard to change their unconstitutional habits." |

Perhaps the most inforgivable loss was at Lafanmi Selavi ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) ("The Family Is Life" in Creole), the orphanage for street boys that Aristide founded and ran. The number of homeless children in Haiti has roughly doubled since 1987, according to the orphanage staff, as Haitian life expectancy fell from 54 to 47 years and many parents were killed or forced into hiding by the repression.

("The Family Is Life" in Creole), the orphanage for street boys that Aristide founded and ran. The number of homeless children in Haiti has roughly doubled since 1987, according to the orphanage staff, as Haitian life expectancy fell from 54 to 47 years and many parents were killed or forced into hiding by the repression.

In 1988, the orphanage was torched by unknown arsonists, but no one died. Afterwards, the staff decided to relocate to a middle-class neighborhood so that street kids could become more visible as "contributing members of the community," according to Joan Keogh, an American who serves as administrator there.

Kids in Lafanmi Selavi receive schooling and vocational training, says Keogh, and the staff spends a lot of time talking to the boys and involving them in decisions about the school and their lives. Mildred Trouillot, a lawyer who has been named by Haitian papers as Aristide's fiancée, teaches older students about the constitution and children's rights here, according to Keogh.

Then in February 1991, five days before Aristide's inauguration as President, arsonists struck again. This time four children died in the fire. A staff member who went back in repeatedly trying to save them also lost his life. The orphanage staff believe the fire was started by agents of the military.

The perpetrators have never been brought to justice, and they are not likely to be, according to Jean-Role Jean-Louis, a 27-year-old Haitian law student who volunteers at the orphanage. "It's going to take time," he said. "Seventy to 80 percent of the judges are holdovers from the Duvalier dictatorship or the coup, and it's hard to change their unconstitutional habits. We're going to need more political stability before we can achieve a functioning justice system."

| "This mafioso private sector has robbed the Haitian people through smuggling, drug-dealing, government subsidies, non-payment of their taxes, ... " |

A lot of justice is waiting to be done. On the wall of

a soccer field next to Ron Voss's house is painted an inscription in Creole:

"This field is dedicated to the memory of Antoine Izméry ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , who gave

his life for democracy September 11, 1993. No to violence! No to vengeance!

Yes to justice! Yes to reconciliation!"

, who gave

his life for democracy September 11, 1993. No to violence! No to vengeance!

Yes to justice! Yes to reconciliation!"

Izméry, a Haitian citizen of Palestinian extraction, was an unlikely candidate for the death squads. "He was one of the richest people in Haiti," recalled Voss, who became his close friend and now manages Izméry's former home as a guest house and religious center. "But he burned his money the right way: he gave it away to good causes."

|

statue of Antoine Izméry ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif)

|

His ultimately fatal cause was the presidential campaign of Aristide. Izméry was Aristide's most prominent financial backer, and spoke out publicly in support of Aristide and against his own class. In 1993, he told a Haitian paper, "This mafioso private sector has robbed the Haitian people through smuggling, drug-dealing, government subsidies, non-payment of their taxes, and all that, so that now they have the capital to buy up the state industries with the money they have stolen." His brother, Georges, was assassinated in 1992 by the death squads.

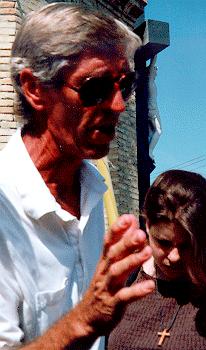

On September 11, 1993, Voss, a tanned, athletic man who could pass for a tennis pro in another place and time, accompanied Izméry to a mass to commemorate the St. Jean Bosco massacre. Only a small group of foreign journalists and human rights advocates dared to attend the event, as the military routinely attacked this sort of gathering during the coup period. Izméry told Michael Norton of the Associated Press that he had been warned by a police special agent that there would be bloodshed if the mass went ahead.

During the mass, a man with a walkie-talkie and a large pistol led a dozen men into the church. They pulled Izméry up to the altar and put the gun to his head, Voss said. Then they dragged him out into the street and shot him in the head. They killed a passer-by who had witnessed the crime, then went on a rampage through the area, attacking people at random. Voss and other witnesses believe the killers were plain-clothes police.

|

Ron Voss ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif)

|

The list of other friends and supporters of Aristide who lost their lives goes on. Guy Malary, appointed Justice Minister by Aristide after the Governors Island accord of 1993, was gunned down shortly after Izméry in 1993, less than a block from where Izméry fell. Father Jean-Marie Vincent, Aristide's close friend, was murdered in 1994 by the same paramilitary attachés.

This November, two young members of Parliament close to Aristide, Jean-Hubert Feuille et Jean-Gabriel Fortune, were gunned down by assassins opposed to the President, setting off a wave of protests in which seven people died.

Human rights groups estimate that 3,000 to 4,000 Haitians were murdered by the coup régime, but there were probably many more uncounted deaths in the countryside. Others perished in unseaworthy boats trying to escape the carnage, and thousands went into hiding within Haiti.

Perhaps the only miracle is that Aristide has nearly lived out his term in office. He survived assassination attempts in 1986 and 1987, and his death at the hands of General Cédras in 1991 was reportedly prevented only by the intervention of the French ambassador and other diplomats. The goal of the St. Jean Bosco massacre as well was almost certainly to kill this troublesome priest. His escape has taken on a miraculous aspect in popular art, according to Voss. In one painting, he turns into a dog and runs away; in another, he is transformed into an angel and flies up to the top of his church.

Peter Costantini is Seattle correspondent for Inter Press Service, a news wire based in Amsterdam. He has previously covered elections in Mexico and Nicaragua.

|

|

|

Father René Soler

|

Best viewed with an HTML 3-compatible browser capable of

table backgrounds, background sounds and client-pull animation.

Last updated: June 9, 1996. © 1996 Peter Costantini (Peter_Costantini@msn.com)