| | | | THE $1.4 BILLION project, scheduled to break ground next year, will construct deep-water container ports and free-trade zones on the Caribbean and Pacific and connect them with a 210-mile high-speed railroad. The Caribbean terminus will be at Monkey Point, where nearly a century ago a German consortium tried, but failed, to build a similar line.

For North American consumers and businesses, the dry canal will reduce shipping costs, said Don Bosco, president of the private consortium that will build and run the system. After two decades of conflict, he said, “Nicaragua is open for business with the rest of the world.”

The dry-canal proposal, while facing competition from proposed land bridges across other parts of Central America, enjoys support across the Nicaraguan political spectrum and indifference in Washington. “What’s there to be against?” said a U.S. diplomat in Managua, welcoming the increased trade and reduced illegal immigration that could result from cheaper transport and new jobs.

Once again, financial backing for the project is coming mainly from European and East Asian firms. But this time, the riptides of global trade have eroded the Monroe Doctrine, which claimed Latin America as the United States’ “back yard.” Latin America countries are increasingly looking east and west for trade and investment

CONTAINER TRADE BOOMS

The seeds of the dry-canal plan germinated in the fertile container trade between Asia, North America and Europe, which since 1990 has increased 6 to 8 percent yearly. The aging Panama Canal, which will revert to Panamanian management in 2000, has become a bottleneck, with waits of several days common. The bigger container ships now being built, known as post-Panamax, are too big to fit through the Canal’s locks. “The international interests that are moving cargo between the Far East and the U.S. and Europe see that the opportunity to have alternatives to the Canal is really critical. Because the canal has some major inefficiencies in it,” said economic consultant Emil Combe.

For container traffic, which tends to carry higher-value and more perishable cargoes, the U.S. “land bridge” has grown in the last twenty years into a faster but more expensive alternative to the Canal. Consumer electronics from Korea, for example, can appear on shelves on the East Coast up to a week earlier — for about $500 more per container — if shipped to Tacoma, Wash., or Oakland Calif., and rapidly loaded onto double-stack rail cars.

Bosco claims the route across Nicaragua to the U.S. East Coast can cut the U.S. land bridge’s price tag per container nearly in half, while remaining “competitive” on shipping time. Some transport analysts, though, say U.S. railroads are in strong financial shape and will be formidable competitors.

Over the past ten years, according to Combe, a lot of manufacturing has migrated southward from Japan to southeastern Asia. For container cargo from this region to the eastern United States and Latin America, he said, a sea-land-sea route across Central America might prove profitable. Shippers could gain economies of scale by moving product across the Pacific in big post-Panamaxes, transferring it into smaller feeder vessels at both ends of the dry canal for journeys north, south and east.

OBVIOUS ATTRACTION

For Nicaragua, the region’s poorest country, the attraction is obvious. Juan Carlos Rivas, the Nicaraguan executive director of the consortium, said, “It will change forever the image of Nicaragua as an unstable, conflict-plagued country to one of a country at peace and in full development.”

But there are significant environmental concerns. Because of Nicaragua’s need for economic help, Nicaraguan environmentalists are more skeptics than opponents.

“Poverty is Nicaragua’s principal environmental problem,” environmentalist Hector Mairena said. “Neither the Suez Canal nor the Panama Canal solved the problems of poverty in those countries.”

The planned railroad will pass through a volcanic zone and near a rain forest preserve, and the ports will be located not far from coral reefs in the Caribbean and sea turtle nesting beaches on the Pacific. Vice president Paul Gilbert of Parsons Brinckerhoff, the engineering firm leading the feasibility study, said the consortium will work to minimize the project’s impacts on these areas.

SKEPTICISM OF PROJECT’S CHANCES

Some analysts, however, are skeptical about the project’s economic feasibility. “These same outfits came here with the idea of selling the Costa Ricans big on this,” said Costa Rica-based transport economist Warren Crowther. “My hypothesis is that these guys are really more interested in getting feasibility studies done and getting consulting fees than in getting any dry canal done.” CINN’s Bosco responded: “I don’t make any money on the studies. I have to break my tail to go out and raise the money for the studies.”

Don’t underestimate the competition, Crowther warned. Indeed, Panama, with existing port facilities and a coast-to-coast distance about a quarter that of Nicaragua’s, may hold most of the trump cards in the dry canal game. Kansas City Southern Railroad is negotiating with the Panamanian government to build a new railroad line on an abandoned right-of-way.

At Manzanillo on Panama’s Caribbean coast, Stevedoring Services of America’s new $120-million container terminal is thriving. Managing director Andy McLauchlan said larger vessels and increased competition have nearly halved costs per container from Asia to Panama in the past three years.

Mexico, too, could offer attractive land-bridge alternatives and big local markets, if it can modernize its ports and railroads and calm its political and economic turmoil.

|

|

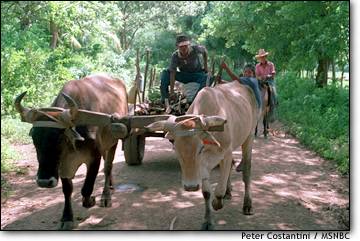

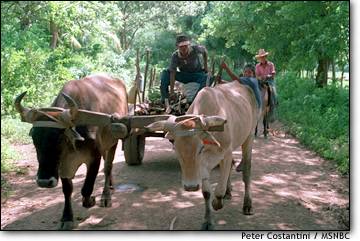

| Poor roads make ox carts practical in parts of rural Nicaragua.

| |

DREAMS OF DEVELOPMENT

Many Nicaraguans across the political spectrum look to the dry canal as an economic cornucopia — newspapers there have claimed it will create 20,000 jobs. After construction, Bosco estimated, the dry canal’s permanent operations will employ 6,000 to 7,000, with each direct position generating another two or three support jobs. Even Daniel Ortega, leader of the Sandinista opposition, supports the project.

With unemployment over 50 percent, and 70 percent living in poverty, a common Nicaraguan response to questions about the project was to rub thumb against index and middle fingers to indicate the cash they hoped the project would spread around.

In the isolated spots where the new ports and free-trade zones will be built from scratch, most people survive on subsistence farming and fishing. In the village of El Gigante, the proposed Pacific site, some saw the new roads as a boon in getting their produce or catch to market.

|

|

| A father and son walk on the beach at Monkey Point.

| |

At Monkey Point on the Caribbean, in a region where some 80 percent are unemployed, many welcomed the prospect of more work and better transportation. But most of the English-speaking Creole people and Rama Indians who live there have no title to their land, which they hold in common. Some fear that the megaproject will pave over their traditional ways of life.

“Sure the dry canal is coming, but then it mustn’t molest the Indians,” said Angela Benjamin MacRae, a Rama Indian, in English. “Leave the Indians to their place. My parents were born right here, right here.” And her neighbor, Cristina Nat, added in Rama: “We’re not against the canal, but we want our rights and our homes.”

Peter Costantini writes on Central America for MSNBC.

| |

See and hear how the proposed canal will impact the people and territory at Monkey Point.

See and hear how the proposed canal will impact the people and territory at Monkey Point.

Panama Canal Commission

Panama Canal Commission