|

|

|

The elections in Ti Rivyè

|

Heavy drums, many hands |

| by Peter Costantini | Seattle | February 28, 1996 |

| beginning |

|

Clubs

Gashes Roosters Bullets |

|

Ballots

Gourdes Bucks Grassroots |

|

Spirits

Hoops Hands |

|

end |

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

One notices a peasant in a straw hat working in a field next to

the airport: "See that guy? He's carrying something and he

looks fucking tired."![[photo of man and Haitian flag]](photos/flagman1.jpg)

American Airlines Flight 268 picks up speed for takeoff from Port-au-Prince ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) . Sitting behind me, two young Canadian soldiers from the UN peacekeeping force are heading home to Alberta on leave. "Can't believe I'm gonna see this island shrink in my face. Came in August, four fucking months."

. Sitting behind me, two young Canadian soldiers from the UN peacekeeping force are heading home to Alberta on leave. "Can't believe I'm gonna see this island shrink in my face. Came in August, four fucking months."

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Clubs

Walking in central Port-au-Prince a couple of days before Christmas, I notice demonstrators at the entrance to the Ministry of the Economy and go in to investigate. About 75 ragged people are shouting angrily. I pull out my camera and snap a picture.

The instant the flash goes off, the group wheels and surrounds me, asking in Creole who the hell I am. I'm a journalist, I reply in French. Why are they demonstrating? They say they're unemployed people trying to get their benefits. "We can't feed our children, we can't have Christmas for our families." They ask me to talk on their behalf to an official, but the receptionist says he's not in.

Just then the vanguard of a much larger crowd bursts in the door chanting and waving leafy branches, symbol of Lavalas ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , the social movement of Haiti's poor. A few men with wooden clubs whale on the stone pillars and wrought iron gates of the Ministry in a fury, like Parisians storming the Bastille.

, the social movement of Haiti's poor. A few men with wooden clubs whale on the stone pillars and wrought iron gates of the Ministry in a fury, like Parisians storming the Bastille.

Then they notice me and move towards me, pounding their clubs on the floor. Feeling like Louis XVI, I duck behind a pillar with a couple of Haitians, who wave their hands and yell "Li se journaliste!" A large melon flies past us and shatters. Frenzied men batter the pillar we're cornered behind. Finally the crowd around the door ebbs, and my volunteer bodyguards pull me out into the street.

Around the corner, a smaller group of men bash a chain and padlock securing a side gate with rocks. Two little boys do a dance mimicking them, laughing as the men curse loudly. After five minutes, the lock still doesn't yield.

On the edges of the crowd, I talk to some demonstrators who have clustered around me. The larger group is public employees who say they haven't been paid for three months. One after another they speak their piece, faces clenched, hands growing eloquent, then turn away in frustration. "The government is full of macoutes" ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) (henchmen of the departed dictatorship), they say. "President Aristide should fire them. They owe us the money, we know they have it. We can't live like this."

(henchmen of the departed dictatorship), they say. "President Aristide should fire them. They owe us the money, we know they have it. We can't live like this."

|

An infrastructure-eating virus appears to have trashed the water, electrical, phone, education and health-care systems. |

Most of the demonstrators don't know much about president-elect René Préval ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) . But one man is wearing a Preval Prezidan T-shirt. "Ti Rene did a good job when he was prime minister before. He'll try to make things better, but he can't do it alone: the people in the ministries need to get it together. We can't wait." When a blue pickup truck full of uniforms and rifles pushes through the crowd, a demonstrator reassures me that the new police don't fire on demonstrators any more like the Army did.

. But one man is wearing a Preval Prezidan T-shirt. "Ti Rene did a good job when he was prime minister before. He'll try to make things better, but he can't do it alone: the people in the ministries need to get it together. We can't wait." When a blue pickup truck full of uniforms and rifles pushes through the crowd, a demonstrator reassures me that the new police don't fire on demonstrators any more like the Army did.

Later, the Ministry's budget director tells me the demonstrators were confused. Unemployment payments come from a different ministry, and the public employees work for the city, so both groups came to the wrong office. Are there corrupt people in his ministry? "I don't hire macoutes, I hire competent people who are willing to work. These demonstrators have problems, I understand that, but they need to look elsewhere for solutions."

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Gashes

![[a borlotte]](photos/borlot1.jpg)

|

| a borlotte |

We all have problems. Haiti in December 1995 has gaping, putrescent gashes. Before the illegitimate government of General Raoul Cédras ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) was removed by U.S. forces in October 1994, it ripped out the plumbing from the main government buildings—a gesture that might play well in our Congress. In three years, it killed more than 4,000 Haitians and exiled hundreds of thousands.

was removed by U.S. forces in October 1994, it ripped out the plumbing from the main government buildings—a gesture that might play well in our Congress. In three years, it killed more than 4,000 Haitians and exiled hundreds of thousands.

After three years of coup d'état, an infrastructure-eating virus appears to have trashed the water, electrical, phone, education and health-care systems. Garbage is piled in big mounds in the streets of Port-au-Prince, constipating traffic and menacing public health. A taxi driver named Nestor tells me: "The garbage heaps block traffic, they're a menace to public health. They've got to pick them up, but that's going to cost time and money. And people just go on throwing garbage in the street. We have to teach them not to do that. It's going to take a lot of education and a lot of time."

With public services, the government faces a chicken-and-egg situation: it needs to repair the streets and generate more electricity to get more people back to work. But to get the taxes to repair the streets and generate more electricity, it needs to get more people back to work. And it's starting from a level that beggars statistics.

The most profitable colony in the world in 1789, Haiti is now the poorest country in the hemisphere. Out of 1,000 babies born, 108 die as infants. Those that survive can expect to live 45 years, about 30 years less than Americans. Only one in four can read and write. The average individual income is $230 a year, roughly a week's pay at U.S. minimum wage. Sixty-six percent of total income goes to the four percent of Haitians at the top of the heap, while only 20 percent of total income goes to the 80 percent at the bottom.

CIA Fact Book 1995, Haiti

During the last year of the coup, the Haitian economy shrank 30 percent and unemployment swelled to around 70 percent. This doesn't mean that people don't work: rather, old and young hit the streets selling chiclets or shining shoes, or try to scratch out a living from tiny plots of exhausted soil.

"For Haiti, agriculture is the key," says Nestor the taxi driver. "They say that Haiti is a nation of farmers, but that's not true any more. The hills are deforested, the soil is worn out, so the peasants have to leave their land. They come into the city and end up in the bidonvilles ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) in impossible conditions. It's really disheartening."

in impossible conditions. It's really disheartening."

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Roosters

The roosters and pigs are doing all right, though. In Port-au-Prince, roosters don't begin to crow just before dawn. On the good nights, they start warming up around eleven o'clock at night and really find their chops at one or two. Scrawny dogs weigh in brassily, goats bleat like tenor horns, and pigs glissade from bass grunts to coloratura squeals.

The nights in Port-au-Prince are one long, headache-inducing jam. Then the next day, you see the roosters red-eyed and unshaven, scratching in the garbage heaps for a hangover cure, and the pigs sleeping it off in the open sewers.

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Bullets

As hard as life remains for most Haitians, it has improved since U.S. forces returned President Jean-Bertrand Aristide ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) to power. His most popular act—against Washington's opposition—has been to abolish the 7,000-man Forces Armées d'Haïti (FAd'H)

to power. His most popular act—against Washington's opposition—has been to abolish the 7,000-man Forces Armées d'Haïti (FAd'H) ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , the gangbangers and drug smugglers who impersonated an army and swallowed half the country's budget. Aristide turned over the old Army headquarters, right across from the National Palace, to the Ministry of Women's Affairs.

, the gangbangers and drug smugglers who impersonated an army and swallowed half the country's budget. Aristide turned over the old Army headquarters, right across from the National Palace, to the Ministry of Women's Affairs.

Since 19 years of occupation by U.S. Marines ended in 1934, the FAd'H was supplied and trained by the U.S. and many of its leaders were trained at our School of the Americas. Paramilitary death squads, too, have been funded and used by the CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency, according to The Nation, the New York Times, and 60 Minutes. The Clinton administration has continued to protect the hitmen, refusing to return over 160,000 pages of Haitian documents seized from FAd'H and death squad headquarters without first deleting the names of American agents.

Haiti Archives, Americas History section of World History Archives

"Before, these strong men, their word was the law," says Nestor the taxi driver. "You kept your mouth shut"—he makes a cross on his lips with one finger. "Now you can speak freely. The macoutes are still all around with big guns, but for now they're laying low."

"The seven thousand soldiers of the Army are still here," says Father René Soler ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , a French priest who has worked with Haitians for 28 years. "They've lost their jobs and they're angry. Just across the border in Santo Domingo is [former chief of police] Michel François and over in Panama is Raoul Cédras." The macoutes still surface periodically to assassinate lawmakers and officials close to Aristide.

, a French priest who has worked with Haitians for 28 years. "They've lost their jobs and they're angry. Just across the border in Santo Domingo is [former chief of police] Michel François and over in Panama is Raoul Cédras." The macoutes still surface periodically to assassinate lawmakers and officials close to Aristide.

Most of the United Nations peacekeeping force of 6,000 (MINUHA ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) is its French acronym) will withdraw at the end of February. Haiti has requested that around 2,000 police and quick-reaction forces remain for six more months, but no U.S. troops would be among them.

is its French acronym) will withdraw at the end of February. Haiti has requested that around 2,000 police and quick-reaction forces remain for six more months, but no U.S. troops would be among them.

United Nations Mission In Haiti - 11/30/94

The 6,000-members of the new National Police which will take over from them are mostly inexperienced, although they include 1,400 former soldiers vetted for a clean human-rights record. The government faces the delicate task of rapidly building the police into a force strong enough to keep the macoutes at bay, but not so strong as to again threaten democracy.

A National Commission of Truth and Justice, established by Aristide to bring the torturers and killers to justice, has stalled in the smoking ruins of the legal system. "It's going to take time," says Jean-Role Jean-Louis, a 27-year-old law student. "Seventy to 80 percent of the judges are holdovers from the Duvalier ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) dictatorship (1957-1986) or the coup, and it's hard to change their unconstitutional habits."

dictatorship (1957-1986) or the coup, and it's hard to change their unconstitutional habits."

According to the Coalition of Haitian Human Rights Organizations, "More than a year after the return of the democratic process, ... the possibilities of recourse for victims of the coup d'état are practically absent." The Coalition implicitly criticized MINUHA for the "failure to dismantle the networks of terror that bloodied the country during the coup, and their possible resurgence after the departure of the multinational forces."

Even if the death squads were disarmed, though, economic power would still remain concentrated in a few wealthy families. Some of them were implicated in funding the 1991 coup and more recent terrorism, and they have never been genteel about defending their privileges.

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Ballots

The elections of 1995 also opened doors for Haitians. On December 17, Lavalas candidate René Préval, who was endorsed by Aristide, was elected president with 88 percent in a clean and peaceful vote. His nearest challenger had 2.5 percent.

![[photo of presidential ballot]](photos/elecpo2b.jpg)

But the December turnout was only 28 percent. For some, Aristide's endorsement of Préval a few days before made the outcome a foregone conclusion. Many abstained because they wanted Aristide to serve out his three years robbed by the coup. The former priest drew 67.5 percent of the vote in 1990 and retains what the New York Times called a "mystical bond with the millions of Haitians who live in want." Others felt discouraged after voting in other recent elections but seeing no concrete improvements in their daily lives.

The new president is a Belgian-trained agronomist who was exiled from Haiti in 1963 by the Duvalier dictatorship. He became friends with Aristide in the 80s while working at an orphanage founded by the latter.

As Aristide's prime minister before the coup, Préval began to clear the zombi cheques ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) (ghost employees) out of the ministries and started a land reform. His "radical tone" made Washington nervous, according to the Haitian paper Le Nouvelliste

(ghost employees) out of the ministries and started a land reform. His "radical tone" made Washington nervous, according to the Haitian paper Le Nouvelliste ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) . But even the Wall Street Journal credits him with a reputation for honesty. His transition team was headed by Chavannes Jean-Baptiste

. But even the Wall Street Journal credits him with a reputation for honesty. His transition team was headed by Chavannes Jean-Baptiste ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , leader of Haiti's most important peasant organization.

, leader of Haiti's most important peasant organization.

Lavalas, literally "landslide" in Creole, suggests a purifying flood washing away the old, corrupt order. Lavalas Political Platform (PPL), the coalition which elected Préval, unites three progressive parties, but the movement is broader and more nebulous than any political grouping. At it's heart are neighborhood, peasant and church groups, the real schools of democracy for poor Haitians.

In voting last summer, the PPL won majorities of 63 percent in the Senate and 81 percent in the Chamber of Deputies. But divisions are surfacing. Some coalition members criticize Aristide's government for making too many concessions to moneyed interests, while others support compromise with them to rebuild the country.

For the three-quarters of Haitians who live isolated from national politics in the countryside, though, perhaps the most meaningful political change occurred earlier this year with the first democratic election of mayors and municipal councils. Before, rural districts had been ruled by iron-handed chefs de section ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) (section chiefs), generally big landowners, appointed by the military. Lavalas won 70 percent of the mayoral races.

(section chiefs), generally big landowners, appointed by the military. Lavalas won 70 percent of the mayoral races.

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Gourdes ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif)

|

President Jean-Bertrand Aristide told the U.S. ambassador, "Men anpil, chay pa lou —Many hands make the burden light." |

![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif)

With the repressive apparatus dismantled and elections held, economic development has eclipsed politics as the critical path. Further advances for democracy will require raising the standard of living and education of the majority of Haitians. Until they can read and write and don't have to spend all their time struggling to survive, too many will remain marginalized from public life. This poverty is not economically sustainable either: if consumer demand is to grow, the desperate four out of five will have to be able to consume. If they cannot, they will begin again to cast off in leaky boats for Florida.

Foreign aid is necessary, says Castor, but not sufficient. "First, the community must participate, people must feel involved and projects must meet their real needs. Second, we need a national project that takes the long view." Years of dictatorship have molded everyone's way of thinking, even within the Lavalas movement. "We need to constantly explain where we're going if we are to develop a new ethics, a new mentality that will lead people to change."

|

"Foreign aid tells us what we have to do. It puts us in a place where we have to say 'Thank you, foreigners, thank you.' It doesn't listen to people's needs." —Harry Nicolas |

The mentality of the United States and international financial institutions must change too, she says. "Change in Haiti is in the interests of the United States. In the post-Cold War period, the United States needs to stop seeing all popular movements as plots against its national security. And the International Monetary Fund must recognize that its actions sometimes impose a burden that people just can't bear. The new government must dialogue with them about reforming the bureaucracy, but the government has to be strong enough to carry out economic and social reforms."

Nevertheless, some see investment opportunities amid the ruins. Chatting over a hotel breakfast, a conservative French businessman is bullish on Haiti: "Everything needs to be rebuilt." After a few years of import-export in Micronesia, he's scouting the French-speaking world for greener pastures. "Clinton needs Aristide's return as a foreign policy victory for the November elections, so he'll prop up the gourde [the Haitian currency] at least through November."

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Bucks

While the people who form Lavalas's base press to improve their lives, international donors demand fiscal austerity. In the wake of the coup's destruction, foreign aid has risen from 45 percent to close to 60 percent of Haiti's budget.

U.S. assistance, often to groups close to the dictatorship, has served mainly to make the cheapest labor pool in the Hemisphere more pliable and accessible. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) head Brian Atwood recently told the Senate that 60 percent of the agency's funds go directly to U.S. businesses—they serve as administrators or contractors for goods and services. In 1991, according to law student Jean-Role Jean-Louis, "USAID spent millions and millions of dollars to stop Aristide's proposal to increase the minimum wage" from $2 to $4 a day. Egged on by Aristide's enemies in the CIA and Congress, the Clinton administration continues to withhold some aid to twist his arm.

"Foreign aid tells us what we have to do," says Harry Nicolas ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , an organizer with peasant groups. "It puts us in a place where we have to say 'Thank you, foreigners, thank you.' It doesn't listen to people's needs. It's like the proverb: I'm making a rope and I give you the other end to hold. But while I'm twisting it, you're untwisting it." Development, he says, should focus on basics: "We don't need turkey wings or Miami [imported] rice or even electricity. First we need to take care of land issues and irrigation and roads and develop local agricultural production. We need to pick up all the trash out there and use it to make bio-gas for cooking."

, an organizer with peasant groups. "It puts us in a place where we have to say 'Thank you, foreigners, thank you.' It doesn't listen to people's needs. It's like the proverb: I'm making a rope and I give you the other end to hold. But while I'm twisting it, you're untwisting it." Development, he says, should focus on basics: "We don't need turkey wings or Miami [imported] rice or even electricity. First we need to take care of land issues and irrigation and roads and develop local agricultural production. We need to pick up all the trash out there and use it to make bio-gas for cooking."

The U.S., the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are pressuring Haiti to sell off nine government-owned firms, including the telephone and electric companies, as part of a Structural Adjustment Plan—a market-flavored recipe for downsizing governments. Privatization touches a raw nerve for many Haitians. Supporters say it is a necessary price to pay for international funding and a way to modernize dysfunctional sectors of the economy. Opponents believe it will increase the power of the elites and the suffering of the poor, pointing to fire sales of public assets elsewhere in Latin American and in Eastern Europe.

In 1993, wealthy Aristide backer Antoine Izméry ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) told a newspaper: "This mafioso private sector has robbed the Haitian people through smuggling, drug-dealing, government subsidies, non-payment of their taxes, ... so that now they have the capital to buy up the state industries with the money they have stolen." Izméry was assassinated by paramilitaries later that year.

told a newspaper: "This mafioso private sector has robbed the Haitian people through smuggling, drug-dealing, government subsidies, non-payment of their taxes, ... so that now they have the capital to buy up the state industries with the money they have stolen." Izméry was assassinated by paramilitaries later that year.

In a plan presented last January to international donors, the Aristide government said that privatization should democratize property, not concentrate it further. It emphasized that any plan would have to be publicly debated. Then last fall, Aristide halted bidding on a state-owned flour mill and cement plant, and refused to sign an agreement with the World Bank and IMF. Over one hundred million dollars in aid still hang in the balance.

|

"There are so many things that need to be done here. The roads are so rocky and bumpy. And there are so many without work. They should be to work fixing the roads." —Immacula Alvares |

Incoming President Préval recently said he would not bow to "ultra-liberal" demands on privatization. But the cement and flour plants, closed down under the coup, are draining government funds. "Wouldn't it be better to look for private capital," he said, "instead of using state money which could serve for something else?"

The pressures are as inexorable as gravity. In this Ptolemaic economic universe, Haiti is an investors' paradise of light-assembly plants revolving around the United States. It exports agricultural products for the whims of the North, but imports its basic food needs. Its orbit is controlled by international markets, so soft persuasion with financial teeth becomes more cost-effective than hard military repression. As investment flows to the cheapest wages, Northern workers share the insecurity.

Under this system, poor nation-states are only theoretically sovereign. They become an echo of the borlottes ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , the brightly-painted lottery booths where Haitians place bets based on their dreams. The military used to run corrupt national lotteries. Now the borlottes primarily use winning numbers from the New York State Lottery, which people can confirm on TV.

, the brightly-painted lottery booths where Haitians place bets based on their dreams. The military used to run corrupt national lotteries. Now the borlottes primarily use winning numbers from the New York State Lottery, which people can confirm on TV.

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Grassroots

Although privatization would favor the wealthy, Haiti does need structural change, says economist George Werleigh ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , advisor to the government and husband of outgoing Prime Minister Claudette Werleigh

, advisor to the government and husband of outgoing Prime Minister Claudette Werleigh ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) . Although privatization and structural adjustment are conceived in the interests of the wealthiest families, he says, Haiti needs an alternative project of structural change. "After three years of the putsch, the elite has milked the cow to the bone and there are no financial resources left in Haiti to impulse development." He looks to overseas Haitians and civil society in North America and Europe as funding sources.

. Although privatization and structural adjustment are conceived in the interests of the wealthiest families, he says, Haiti needs an alternative project of structural change. "After three years of the putsch, the elite has milked the cow to the bone and there are no financial resources left in Haiti to impulse development." He looks to overseas Haitians and civil society in North America and Europe as funding sources.

|

The African world-view "sees ourselves as part of the universe, as a force among forces" seeking harmony. —George Werleigh |

Public spending, Werleigh believes, should be channeled mainly into agrarian reform that promotes small-scale farming, processing and marketing, and develops human resources. Changing the structure of land ownership means not only redistributing land, but also encouraging smallholders to pool resources and providing just settlements of land disputes. "The land worker," he says, "should be the land owner."

Land reform could also help reverse Haiti's severe deforestation, which forms a vicious circle with social devastation. Cheap imported grain, sometimes provided as foreign aid, and expensive inputs and loans bankrupt small farmers. They cut down trees to sell for fuel, and the exposed topsoil washes down into the rivers, leaving barren hillsides and ruining fisheries. Eventually, those who can't survive leave for the city or Miami. After decades of this cycle, people still work 43 percent of the land, but only 11 percent is technically arable.

In the rice-growing Artibonite ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) Valley, however, peasant cooperatives are pooling resources to reforest bare hillsides and work the land more efficiently. They also carry out potable water projects, develop alternative energy sources, and train members in health care. With a small loan from a non-profit development bank, one group recently built a silo to store their grain so they are not captives of the low price at harvest time.

Valley, however, peasant cooperatives are pooling resources to reforest bare hillsides and work the land more efficiently. They also carry out potable water projects, develop alternative energy sources, and train members in health care. With a small loan from a non-profit development bank, one group recently built a silo to store their grain so they are not captives of the low price at harvest time.

Members have died in conflicts with big landowners, organizers say, and local courts are still dominated by military-appointed judges. The local water authority is also corrupt, so they are raising their own money for irrigation pumps so they can expand the area under irrigation.

Genuine development also percolates through slum-dwellers associations in Port-au-Prince's bidonvilles, warrens of burnt out cars, open sewers and malnourished children. Here, a heavily armed new gang of ex-soldiers and paramilitaries called the Red Army intimidates the newly trained police force. Yet in the face of the most difficult conditions, ti kominote legliz, Christian communities which practice liberation theology, are "trying to find a way to live like humans in this country," as one member put it. They combine Bible study with mutual support, because "sharing food is a kind of communion."

|

"[Jesus] found a balance between reason and mystery. But everyone can become like him" —Lolo of Boukmans Eksperyans |

The groups sponsor an artists cooperative and a sewing center. "Work means freedom and respect," says another member. "If we could work, we could have a place to live, we could eat. Work means respect." In one area, community pressure has helped win a new water tower and sewers.

Haiti has a high percentage of women who are heads of households, says Suzy Castor. They play an important role in grassroots groups and dominate the informal economic sector. Many are market women, she says, who "are more open to modernizing than men and have more cash flow, which gives them more freedom than in many societies."

Despite a typically hard life, Immacula Alvares has emerged as a dynamic force in her community outside Port-au-Prince. After raising seven children with her late husband, she sewed baseballs for thirteen years and cleaned houses for five. Finally, with a couple of dollars loaned by a friend, she started a small business selling bread. Then, with the help of an American ex-priest, Ron Voss, she turned her home into a non-profit health clinic for her neighborhood.

"Here, if you're poor, you have to pay the doctor and pay for medicine, or they won't treat you," she says. With Voss's support, she recently built a new house for the clinic, which receives supplies and volunteers from North America. A doctor comes every day and a dentist twice a week, and no one is turned away.

"There are so many things that need to be done here," says Alvares. "The roads are so rocky and bumpy. And there are so many people without work. They should be put to work fixing the roads. And there is so much garbage. It clogs the gutters, and then when it rains the water overflows and ruins the road. People have to take responsibility for cleaning up around their houses."

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Spirits

|

|

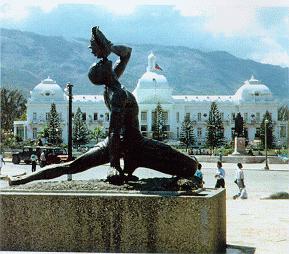

"le Neg Marron" (the Runaway Slave): statue on the Champs de Mars with the National Palace in the background —photo by Joe Heckel |

Alvares' clinic, the base communities and the rural cooperatives all draw on the African tradition of konbit ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) —unpaid communal work—which has survived in the countryside. George Werleigh traces its lineage back to the marrons

—unpaid communal work—which has survived in the countryside. George Werleigh traces its lineage back to the marrons ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) , slaves who escaped into the mountains. They never internalized slavery or recognized the French slaveholders' legitimacy, he says. Rather than seeking to dominate the universe, the African world-view "sees ourselves as part of the universe, as a force among forces" seeking harmony.

, slaves who escaped into the mountains. They never internalized slavery or recognized the French slaveholders' legitimacy, he says. Rather than seeking to dominate the universe, the African world-view "sees ourselves as part of the universe, as a force among forces" seeking harmony.

African grammar and words mix with French vocabulary in Creole, the daily language of most Haitians. African and pre-Columbian Taino gods also survive in vodou ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) . The dictator Papa Doc Duvalier

. The dictator Papa Doc Duvalier ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) used symbolism from the indigenous religion to terrify people, wearing a black hat like Baron Samedi, the lord of the cemetery, and talking in a nasal voice like a zombi

used symbolism from the indigenous religion to terrify people, wearing a black hat like Baron Samedi, the lord of the cemetery, and talking in a nasal voice like a zombi ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) . Yet vodou has survived tyrants and missionaries to encode Haitians' yearnings.

. Yet vodou has survived tyrants and missionaries to encode Haitians' yearnings.

"In vodou, Jesus is franc guinée ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) [self-realization and harmony], he found a balance between reason and mystery. But everyone can become like him.," says Lolo, member of the popular band Boukmans Eksperyans. "Rather than talking about sin, we talk about a loss of energy. Vodou knows that the spirits that appear in people are archetypes. It puts us in contact with them and helps the community confront "jealousy, hate, vengeance, the spirits that eat our energy, so we can lose our anger and arrive at pure energy."

[self-realization and harmony], he found a balance between reason and mystery. But everyone can become like him.," says Lolo, member of the popular band Boukmans Eksperyans. "Rather than talking about sin, we talk about a loss of energy. Vodou knows that the spirits that appear in people are archetypes. It puts us in contact with them and helps the community confront "jealousy, hate, vengeance, the spirits that eat our energy, so we can lose our anger and arrive at pure energy."

Vodoun (or Voodoo) Information Pages

This spirituality permeates Haitian life in subtle ways. When organizer Harry Nicolas visited New York recently, what struck him most was how Americans "run around in their cars, eat very fast, no time to talk with each other. On the subway, they look like zombis. I felt pity for everyone. They think all that shiny stuff is God." But Nicolas was impressed with how accessible information is in the States. "Public information doesn't exist here. Information is used as a tool for power. What I really liked in the States was the organization, not the big houses with all the appliances."

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Hoops

In Port-au-Prince, little boys still play with hoops made from bicycle rims. The boys carry them with a coat-hanger wire hooked at one end. They start the hoop rolling and whip it along with the hooked wire.

The boys roll their hoops over rocks and ruts, but the hoops don't fall down. At least I didn't see them fall. They lash them along with finesse at full gallop, faces flat with concentration, and boys and hoops become mythical creatures with one wheel and two legs, half animal, half vehicle. Port-au-Prince is short on smooth surfaces, but the hoop-boys glide over decades of erosion and neglect on a cushion of insouciance.

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

![[bottom]](./art/bottom1.gif)

![[down]](./art/down1.gif)

Hands

![[Immacula Alvares]](photos/immacul1.jpg)

|

Immacula Alvares ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif)

|

Nestor the taxi driver takes me to the airport on a new road that skirts the city to the north. We skim over smooth asphalt with shapely drainage, all done in the past year, he says. The road runs past Aristide's home—Nestor points out the gate. The hills on either side are bare. "The city is packed, no more room. Now that the road is done they're going to have to build some new neighborhoods out here, some new businesses."

From the air, Haiti's landscape looks so vulnerable: bony, convoluted mountains chipped away by ochre quarries, parting for a moment to reveal the luminous green rice paddies of the Artibonite, finally crumbling down in the north to white-sand beaches scalloped with clear turquoise. I wonder when these beaches will cease being escape hatches.

A piece of my heart stays behind with the Haitians working to reclaim this place for their own. In 1990, the U.S. Ambassador warned Aristide with a proverb, "Apre bal, tanbou lou ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) —After the dance, the drums are heavy." Aristide replied with another, "Men anpil, chay pa lou

—After the dance, the drums are heavy." Aristide replied with another, "Men anpil, chay pa lou ![[speaker icon]](art/speaker3.gif) —Many hands make the burden light."

—Many hands make the burden light."

![[top]](./art/top1.gif)

![[up]](./art/up1.gif)

Peter Costantini is Seattle correspondent for Inter Press Service, an news wire based in Amsterdam. He has previously covered elections in Mexico and Nicaragua.

A shorter version of this piece appeared in the February 28, 1996 edition of The Stranger, a Seattle weekly newspaper.

|

|

|

The elections in Ti Rivyè

|

table backgrounds, background sounds and client-pull animation.

Last updated: June 7, 1996. © 1996 Peter Costantini (Peter_Costantini@msn.com)

Background music: "Rhythms of Rapture: Sacred Musics of Haitian Voodoo," produced by Elizabeth McAllister